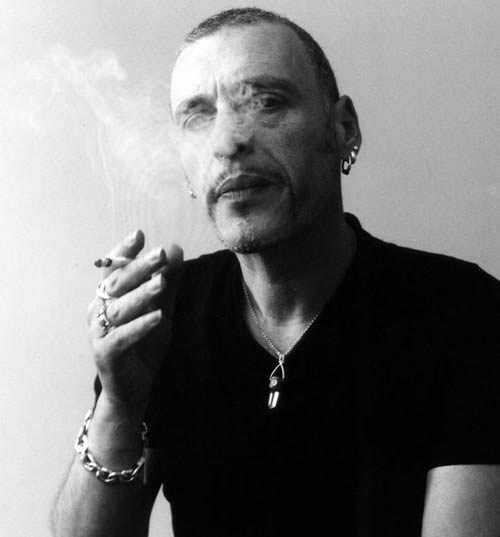

Here’s an interview I did with esteemed music journo Charles Shaar Murray (originally run in Blueprint magazine, now called Blues In Britain) around the time of the publishing of ‘Boogie Man’, his book on John Lee Hooker.

The Captain: The new book….a long hard road you travelled but it’s finally here. Could you give our esteemed readers a rundown on how it all came about?

CSM: When John Lee had his massive comeback with The Healer, he and his manager, Mike Kappus, decided that it was time that a proper, authoritative full-scale biography of John was written since his life and career had never been properly examined before, and the only information about him in the public domain was in a few articles here and there, and on a bunch of often hilariously inaccurate liner-notes. In the immediate wake of the success of Crosstown Traffic and scoring a Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award, I became one of a group of short-listed writers who were considered for the job. Eventually it came down to me and the late Robert Palmer, who’d already written Deep Blues, one of the definitive books on Delta music. He was actually the first choice, as I understand it, but he had two books on the go at the time and was late with both of them. I was initially somewhat daunted, since I’d just spent several years in Jimi Hendrix’s life and had an idea for a novel which I wanted to write, but then I was kidnapped and tortured by Mike Kappus and Pete Townshend, who talked me into doing it. As Mike put it, ‘If you’re capable of writing a novel you’ll be able to do it anytime, but John Lee isn’t necessarily going to be around forever.’ That just about clinched it. I signed the line and agreed to deliver a 100,000-word manuscript in 18 months. Eight years later, Viking Penguin received this THING that weighed in at around 270,000 words.

The Captain: …both ‘Crosstown’ and the JLH book are shot through with cultural references and history of black music….

CSM: Yep. That’s pretty much what I do!

The Captain: Your best writing deals with singular talent…Hooker, Muddy, Alex Harvey, Patti Smith….?

CSM: As a critic, you write about music, and about what the music’s about. As a journalist, you’re drawn to people and personalities. The best stuff happens when you can pull the two together.

The Captain: I guess you don’t have to like em all the time to write good stuff though (thinking here about the ‘Shots’ pieces on Wings-era McCartney and ‘Black and Blue’ period Stones)…?

CSM: Ultimately, you gots to call it like you sees it. I just went in there, and what I wrote is pretty much the way it came down, except that in the case of the Stones piece I had to do all that ‘dream sequence’ stuff because there was so much in there about drug use: mine as well as theirs!

The Captain: Why Hooker? A big influence from the word go?

CSM: The first Hooker music I heard was ‘Dimples’, which was a Top 30 single in ’64, and a couple of older tracks on Pye International R&B series Chess compilations. I came to blues via the Stones and then this compilation called ‘The Blues Volume One’ – you know, ‘start here, kid’ – and there he was with ‘Walkin’ The Boogie.’ I’d never heard music that seemed so strange but felt so right. If you’ll pardon the awful pun, I was hooked.

The Captain: What was on the teenage CSM’s Dansette? And his radio?

CSM: The first record I ever bought was by Cliff Richard, but in my defence I have to state that I was only nine at the time! Then came Elvis, but even then I preferred the ’50s sides I heard on an album belonging to a friend’s older sister to the post-army stuff. Then when I was 12 along came The Beatles and a few months later the Stones, then The Yardbirds, The Animals and The Who, then Motown and Stax, plus I was trying to follow up on the blues, so I guess it was equal parts pop, rock and soul: the standard early ’60s mix.

The Captain: The NME years……a great time to be a music writer, so much happening…?

CSM: Yep, I have to say that it was a wonderful era. ‘Rock journalism’ came of age in the late ’60s and early ’70s as a response to the needs of both the musicians and the audience, but then it seemed as if the party was almost over: all the politics had drained away and idealism had degenerated into hippie cliche. So the new generation of writers championed those few artists who genuinely excited us and agitated for a return to music with some urgency and vitality about it whilst taking the p*** out of former heroes who’d come over all disappointing, like the Stones and ex-Beatles and Lou Reed. And then came punk! For the first time, believe it or not, I was dealing with musicians who were younger than I was!

The Captain: Blast Furnace and the Heatwaves, as much fun as it sounded? Best memories? (The Roundhouse?)

CSM: The Blast band was definitely tons of fun, despite a little too much bickering within the band. The front line of the band stayed the same, but we had rather too many changes of bass player and drummer for my liking. We toured with Wilko Johnson, Joe Jackson, Rockpile and The Pirates, and we opened shows for The Damned, The Clash and the Boomtown Rats. The basic idea of the band was to take the basic Dr Feelgood model of stripped-down, in-yer-face R&B, mix in a hefty dose of MC5 and rev it all up even further until it reached as cranked-up a level of hysteria as the best of the punk bands.

The Captain: You were legally threatened by a disco band about your use of the name Heatwaves!

CSM: Yeah, that was a farce and a half. I’d originally coined the name ‘Blast Furnace & The Heatwaves’ during endless drinking sessions with Alex Harvey, and we’d improvise comedy routines about fictional ’50s rockers and early ’60s beat groups. He was ‘Brett Falcon’, I was ‘Blast Furnace’ and we then expanded it to include their backing groups. Then in 1975 Alex had this Christmas gig at the Apollo in Victoria, and he came up with this idea that he wanted his opening act to be a bunch of music journos. He offered to pay for rehearsals, instrument rentals and beer, so a bunch of us from various papers formed the first Blast Furnace band. We did the one gig, had a laugh and then forgot about it. Fast-forward two years: it’s 1977, everybody in the world has a band, and I meet a couple of guys who’re Feelgoods fans and fancy doing a punky R&B group. They suggest reviving the old Blast name and then Heatwave start hiring m’learned friends and accusing us of ‘passing off’ as them. Well, if I’d wanted to pass a band off as Heatwave, I’d’ve assembled seven black guys in satin jumpsuits and had them play Earth, Wind & Fire knockoffs, but we were five punky looking guys in leather jackets playing amphetamined R&B, so I couldn’t quite see how anybody could get the two bands confused. Nevertheless, they went for it, papered us with writs, and blocked the release of ‘South Of The River’, which we’d had in the can for awhile: we were gigging all over the place and going down great, but we couldn’t put our record out, and that really gutted the band. By the time we’d agreed that it would simply come out as ‘Blast Furnace And?’, the group had pretty much broken up. If we’d got it out earlier we might have had a minor hit, because it sold 6000 copies in the first two or three weeks, which wasn’t massive but it was very respectable indeed.

The Captain: I always though ‘South Of The River’ would’ve made a good cop show theme like ‘Hazell’ or ‘The Sweeney’

CSM: You think you’re going to get an argument on that? I still think it was a very snappy little tune indeed.

The Captain: You got to hang out with The ‘Dublinaires’, and play rhythm guitar with Terence Trent D’Arby?

CSM: The Dublinaires, who sang backing vocals on ‘Can’t Stop The Boy’, a track from our 1977 EP Blue Wave, were Phil Lynott and Bob Geldof, who were mates of mine at the time. Incidentally, the lyrics to that tune were co-written with the poet Hugo Williams, who was also a mate of Wilko’s and collaborated with him on songs like ‘Dr Dupree’. We cut that EP over a weekend at Pathway Studios in Islington, where Stiff cut a lot of their stuff, including Nick Lowe’s ‘So It Goes’ and the first Costello album. Bob and Phil came down on the first day and we had to send them away because we were still doing backing tracks, but they came back the next day. When Phil arrived our bass player lost it completely. He was standing in the studio waiting for the tape to roll and he was saying, ‘Oh, it’s such an honour, I sing along with Thin Lizzy in my car all the time’, and we were just clutching our heads in the control room going, ‘Oh no, for f***’s sake shaddup’. I remember Zenon de Fleur from the Bishops, who was co-producing with fellow Bishop Johnny Guitar, hitting the talkback and saying to Philip, ‘Excuse me Phil, but have you got a cold?’ and Phil replying, ‘No, man, it’s just the way oi sound live’. My other main memory of the ‘Blue Wave’ session was somebody accidentally wiping my guitar solo from that track right at the end, with all the gear packed away and a reggae band banging on the door to get in. I had to borrow Johnny’s Strat, plug it in to the nearest amp, and do a one-take recreation of a solo I’d worked on for an hour the day before. Actually, it ended up better than the one we lost. A little more urgent! As for rhythm guitaring with Terence, I’ve no idea where that little story came from. It’s a wonderful urban myth, but unfortunately it never happened.

The Captain: Late 70s was a great time for Brit R&B (and blues too, my favourite Muddy is on those late 70s Blue Sky albums with Johnny Winter)?

CSM: Hmmm here’s where I p*** everybody off. That era, with the Feelgoods and, subsequently, solo Wilko at the head of it, was the last time anybody did anything genuinely radical or creative with British R&B. The best of the Britbluesers I’ve heard since have been very musical, and a lot of them are Big Fun on a night out, but there’s nothing there that’s really distinctive or which adds anything major to what has gone before. The problem with the R&B scene was that it couldn’t move with the times, and a music that cannot do that won’t be able to top up its audience with younger fans, let alone grow artistically. I wish that Britain could have produced the likes of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Robert Cray – who sparked the last major blues revival in the US – but ’twas not to be.

The Captain: Hendrix and Hooker: you picked two big guys to write about …. anyone you’d like to work on next? Musically oriented or otherwise? Or a novel?

CSM: The next thing is a novel, though not the one I was planning when the ‘Boogie Man’ project came up. That may well get written one day, though in radically different form, but right now I’m trying to finish the one I’m on at the minute. If it turns out good, it’ll be published towards the end of 2000 or the beginning of 2001. If it ain’t, no-one but my agent will ever see it. As for big music biographies, I’d only contemplate doing another one if the subject was fascinating and the money astronomical. Writing books like ‘Boogie Man’ is not a cost-effective activity: on an hourly rate I’d have made more money working at McDonalds.

The Captain: And finally, it says in ‘Shots’ that your favourite cult objects are the Strat, the Mac and the Zippo. Got any more toys lately?

CSM: Nope, the big three still rule. Only these days it’s a different Mac and a different Zippo and, unfortunately, a different Strat. I made the mistake of loaning my salmon-pink ’63 to the wrong person, and it never came back. A gunmetal ’89 Strat Plus is not an adequate substitute. My current pet guitar is a Fender JD Telecaster; I miss the Strat’s wiggle stick, but the JD is the first Fender I’ve ever bought brand new, and it felt perfect the moment I pulled it off the shop wall.